S11, E4B: The B-Side/"Strange Fruit"

Series 11: The Collateral Damage of Revenge in Science

This is a continuation from S11, E3B: The B-Side/"We Didn't Start the Fire" and the B-Side of S11, E4: Bonfire of the Ironies where I continued with Series 11: The Collateral Damage of Revenge in Science.

Welcome to the B-Side

This is a free example of how I plan to put out paid content in the near future. These will be mainly counterparts to free articles, where I go into more depth, talk about the background work or share digressions. See The B-Side Explainer for more information.

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here's a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here's a strange and bitter crop

“Strange Fruit”, Lewis Allan (pseudonym of Abel Meeropol)

Elisabeth Freeman’s Chronology

Following on from S11, E3B: The B-Side/"We Didn't Start the Fire" and over several B-Side episodes in this series, I am going to work through Elisabeth Freeman’s account of the ‘The Waco Horror’ in 1916. Here, using her words, I will set out the background and events leading up to the day of Jesse Washington’s trial.

My hope is also to show you how nuanced the writing in the Crisis report was because that is what made it so influential. It assumes Washington’s guilt while subtly subverting the credibility of that conclusion. Perhaps some who read it at the time thought noticed inconsistencies that the journalist had missed. So much the better when the reader becomes detective.

What was Freeman Telling us about Washington’s Temperament?

After the initial introduction of the name Jesse Washington she puts the reader on first name terms for one sentence only. That is all it takes to humanise him in print.

Jesse was a big, well-developed fellow, but ignorant, being unable either to read or write. He seemed to have been sullen, and perhaps mentally deficient, with a strong, and even daring temper.

“The Waco Horror”, Supplement to the Crisis, July 1916

Then she tells us that he had been involved in an altercation only two days before the murder was committed.

Saturday May 6, 1916

It is said that on the Saturday night before the crime he had had a fight with a neighboring white man, and the man had threatened to kill him.

ibid.

I think Freeman mentions the fight to make a point that someone threatened Washington’s life two days previously rather than as an example of his temperament. I don’t have the necessary information to speculate on this but it is an interesting tidbit.

Monday May 8, 1916

Relaying the account as revealed to her, Freeman writes:

… while Mr. Fryar, his son of fourteen, and his daughter of twenty-three, were hoeing cotton in one part of their farm, the boy, Jesse, was plowing with his mules and sowing cotton seed near the house where Mrs. Fryar1 was alone. He went to the house for more cotton seed. As Mrs. Fryar was scooping it up for him into the bag which he held, she scolded him for beating the mules. He knocked her down with a blacksmith's hammer, and, as he confessed, criminally assaulted her; finally he killed her with the hammer.

ibid.

Remember that this is what Washington is said to have confessed. The doctor did not confirm Mrs Lucy Fryar was sexually assaulted, although contemporary reporting of what he did say, vary. She was certainly killed by blunt force trauma. The family obviously provide each other with alibis as they were working in the fields together. There have been alternative explanations mooted since but not with any supporting evidence.

The boy then returned to the field, finished his work, and went home to the cabin, where he lived with his father and mother and several brothers and sisters.

ibid.

So the official story requires us to believe that after committing a heinous crime for which is knows he would be hanged, he finishes his work for the family of his victim and continues with his day normally, making no attempt to get away or hide. Freeman remarked that he was likely to have been ‘mentally deficient’ but that raises more questions than it answers.

When the murdered woman was discovered suspicion pointed to Jesse Washington and he was found sitting in his yard whittling a stick. He was arrested and immediately taken to jail in Waco.

ibid.

Other accounts suggest he had blood on his clothes and that he claimed it came from a nosebleed. Freeman does not relay why he was the only suspect or who discovered the body despite having sight of the case file.

Tuesday May 9, 1916

… a mob visited the jail […] These were all Robinson people. They looked for the boy, but could not find him, for he had been taken to a neighboring county where the sheriff obtained a confession from him. Another mob went to this county seat to get the boy, but he was again removed to Dallas.

ibid.

She describes the actions taken to evade the mob but then she shows us that the mob were evidently in a position to negotiate terms with the authorities:

… the Robinson people pledged themselves not to lynch the boy if the authorities acted promptly, and if the boy would waive his legal rights.

ibid.

The reporting may seem matter-of-fact by current standards, but the case she made was all the more powerful for it, and could not be overlooked. Any reasonable person reading the story, would have almost certainly wondered why Washington was asked to waive his rights, to avoid an illegal lynching.

In making these stipulations the mob had no fear of repercussions, unaccountability is still a feature of mobs to this day, particularly online.

A second confession in which the boy waived all his legal rights was obtained in the Dallas jail.

ibid.

This suggests he was either entirely ignorant of his rights or he did not have the mental capacity to understand what they were. How can anybody consent to waive their legal rights under such circumstances and be deemed competent to stand trial? Even although fifty men would be deputised, presumably to protect the prisoner, they were never deployed. Again, Freeman states these facts leaving the reader in the role of detective to work out what it means.

Thursday May 11, 1916

The Grand Jury indicted him on Thursday, and the case was set for trial Monday, May 15.

ibid.

Sunday May 14, 1916

Sunday night, at midnight, Jesse Washington was brought from Dallas to Waco, and secreted in the office of the judge. There was not the slightest doubt but that he would be tried and hanged the next day, if the law took its course.

ibid.

Freeman remarks:

There was some, but not much doubt of his guilt. The confessions were obtained, of course, under duress, and were, perhaps, suspiciously clear, and not entirely in the boy's own words.

ibid.

Here, by stating there was ‘not much doubt of his guilt’ she quietly opened to door to there being some doubt. Her remarks on the confessions, including how they were secured and their authenticity, justified those doubts or at least made them credible to the readers.

She added:

It seems, however, probable that the boy was guilty of murder, and possibly of premeditated rape.

I think Freeman and her editor Du Bois, paid close attention to the fact that most of their readers would think Washington was guilty, no matter what was said. So although they discretely reminded readers of the uncertainty they did not challenge the verdict.

They wanted to emphasise that his guilt was beside the point that the brutal retribution was an unjustifiable abomination. Suggesting Washington was innocent would have been a distraction from the far bigger injustice across the US.

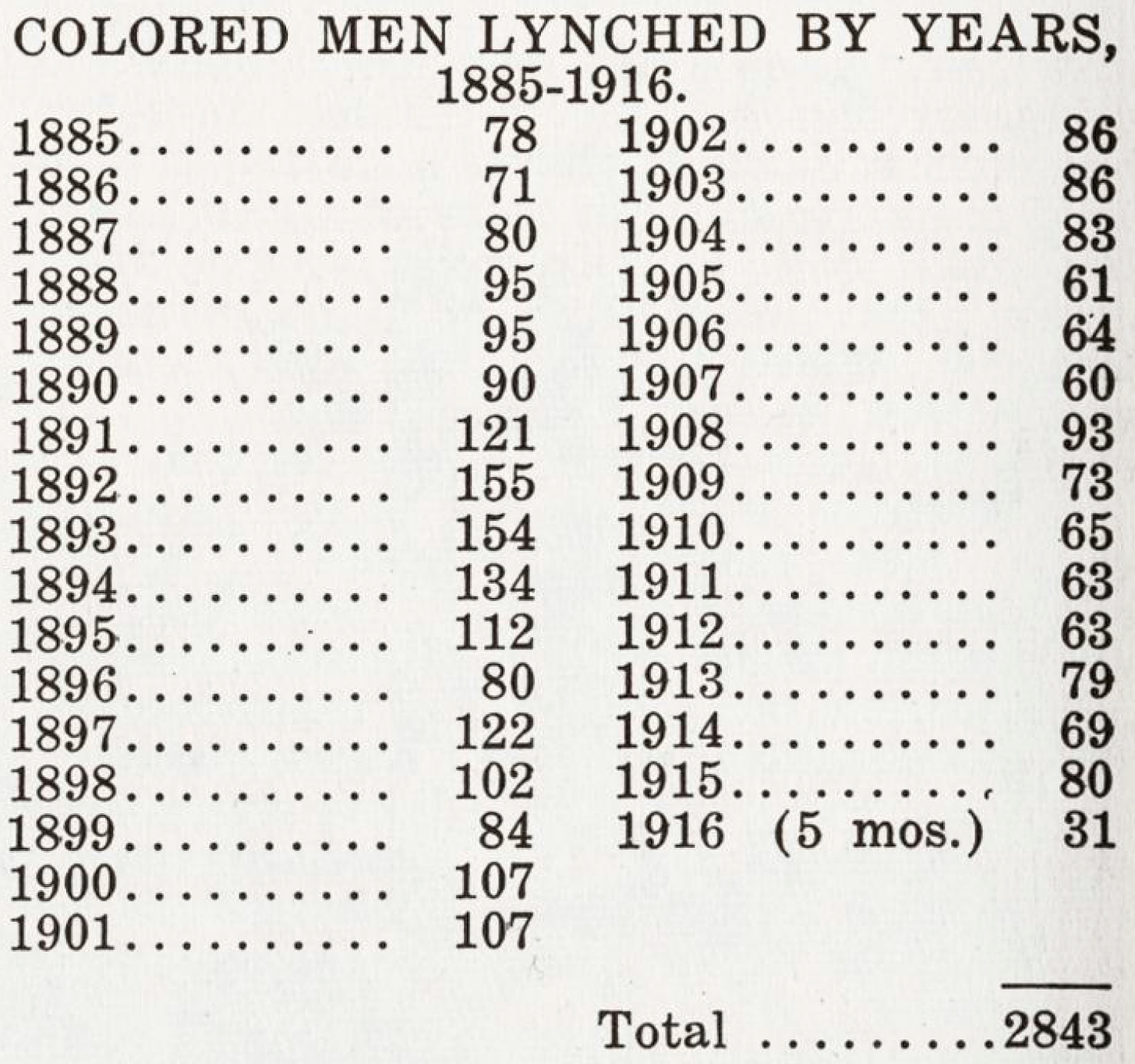

Consequently, the campaign this inspired was not to right unrightable wrongs by exonerating dead people, but to stop the practice of lynchings altogether. The table taken from the published report below shows the state of affairs at the time and what the piece was trying to stop.

Putting these figures into perspective; in the thirty years prior to this atrocity there had been an average of one to three lynchings per week. In some towns, it was politically expedient to facilitate this through the connivance of the courts and law enforcement. This report had a big impact but the threat to Black people remained long afterwards because lynching was seen as a tool of subjugation by instilling fear.

On 21st March 1981, 19 year old Michael Donald was the last person known to be lynched in the USA, just for being black. He went out to buy cigarettes for his sister and was abducted by some members of the KKK.

Others have examined the archives of the Washington case and written books about what they have found. They are therefore in a better position to theorise. My observations are limited to what I gleaned from looking into the Crisis report and its subtext.

We can’t know if Washington committed the crime, but perhaps we can be sure that even if there was irrefutable evidence of his innocence at the time, it wouldn’t have been enough to have saved him from his terrible fate. As I discuss in the next B-Side episode, the lynching was a political event by design, and a means to acquire votes and power.

Next: S11, E5B: The B-Side/The Politics of a Crime

‘Fryar’ appears to be a mistake because in other texts this is given as ‘Fryer’, also, the descendants of that family are known as Fryer.